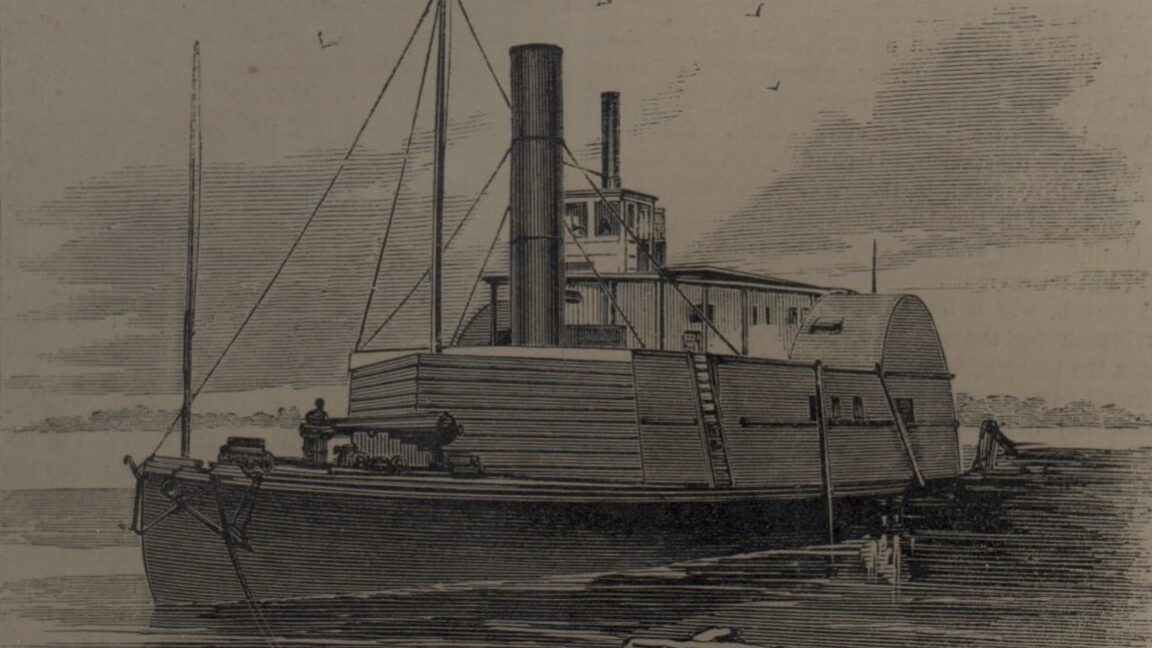

The Steamer Etiwan, built in the 1830s looked very much like the Planter (above)

Dr. Lewis Reeve Sams Jr., the Etiwan, and Robert Smalls

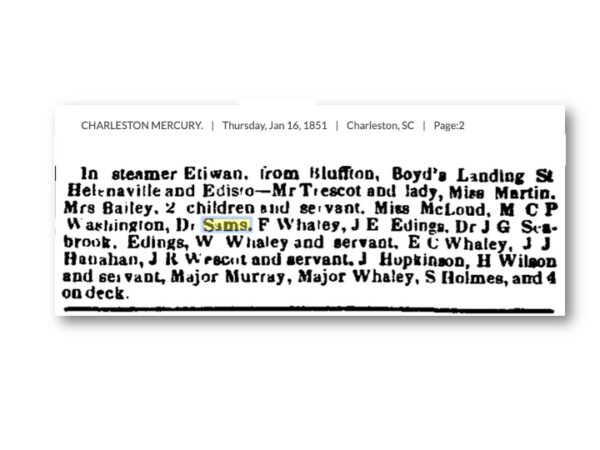

Old newspapers sometimes open unexpected doors. A brief 1851 reference in the Charleston Mercury newspaper to “Dr. Sams” traveling aboard the steamer Etiwan appears minor at first glance. But that small notice links three very different stories: a Sea Island planter-physician, a working harbor steamer, and one of the most daring acts of the Civil War.

In the early 1850s, there were five ‘Dr. Sams’ residing in the Beaufort area. However, since Dr. Lewis Reeve Sams, Jr. was the resident physician and a prominent resident in St. Helenaville with plantations on both St. Helena and nearby Polowana Island, it is highly probable that the ‘Dr. Sams’ in this article was Dr. Lewis Reeve Sams, Jr. (1810–1888).

The Planter’s Shuttle

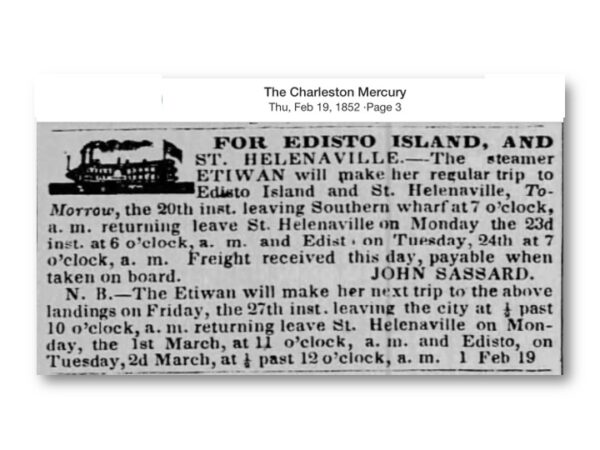

Built in Charleston in the 1830s, the side-wheel steamer Etiwan served as a dependable shuttle between Charleston and the Sea Islands—Edisto, Rockville, St. Helenaville, and Bluffton. She carried cotton bales, trunks, mail, planter families, and the enslaved crews who powered her engines and handled her lines.

Dr. Lewis Reeve Sams Jr. (1810–1888) fit squarely into that world. Resident physician at St. Helenaville and a planter with ties to St. Helena, Polowana, and Datha Islands, he moved comfortably between plantation and city. A routine trip aboard the Etiwan would have been unremarkable in 1851. For men like Sams, the steamboat network was infrastructure—ordinary, dependable, and woven into the rhythms of Sea Island life.

A Harbor Moment That Echoed

In the early hours of May 13, 1862, Etiwan lay moored at North Atlantic Wharf. That night, Robert Smalls—enslaved pilot of the Confederate transport Planter—executed his escape.

Smalls’s wife, children, and the families of other crew members could not safely board at Southern Wharf. They needed a discreet staging point. For a brief, quiet interval, Etiwan became that place.

Hidden below decks, the families waited. An enslaved seaman from Etiwan, later identified as Chisolm, helped guide them through harbor routines he understood intimately. When Planter edged alongside, the transfer was swift and silent. Then Smalls turned downstream, passed the Confederate forts, and delivered the ship, cargo, and families to the Union fleet.

Etiwan did not sail that night. She did not break the blockade. But without her presence—her deck space, her crew, her concealment—the escape may not have succeeded.

Loose Coupling, Stark Contrast

There is no evidence that Dr. Sams ever knew Robert Smalls, although they were both born in Beaufort, South Carolina. Their lives operated in parallel worlds. Yet both depended on the same maritime system—the same harbor routes, the same small steamers, the same skilled Black labor that made movement possible.

In the 1850s, Etiwan carried a physician of the planter class as part of an orderly slave society. A decade later, that same vessel—through its crew and its location—briefly enabled enslaved people to rupture that order from within.

The connection is indirect. It is structural rather than personal. But it is revealing.

An Ending in Familiar Waters

Etiwan’s own story ended in Charleston Harbor when she struck a submerged “torpedo”—a Confederate mine—and was declared a wreck. The channels she knew best destroyed her.

Dr. Lewis Reeve Sams, Jr. (1810–1888) lived to see emancipation undo the plantation world that had sustained his class. In 1866, he moved nearly his entire family to Galveston, Texas, the longtime home of his sister-in-law.

Robert Smalls (1839-1915) went on to become a U.S. Congressman and a national symbol of wartime courage.

Between them sits a modest side-wheel steamer—never famous, rarely mentioned—yet briefly essential to one of the most consequential escapes of the Civil War.

Sources

Harper’s Weekly, June 14, 1862, p. 372

Charleston Mercury, Jan 16, 1851

Charleston Mercury, Feb 19, 1852