Virginia B. Bartels summarizes the history of education in South Carolina very well. “Much of the 300-year history of our public schools is a tragic tale of fits and starts, marked at times by inspired leaders, but too often mired by problems of class, race, war, poverty, and geography.”

I believe receiving a good education is a primary reason so many Sams could rebuild their lives after the Civil War’s devastation. However, they received this education because they were lucky enough to be born into a family that could afford to pay for a good education in a time and in a place where this was not common. The sad state of childhood education in Beaufort in the antebellum era was not about money. You may be surprised to learn that British tradition played a vital, negative role.

Education in the 18th Century

Many of the earliest European settlers in South Carolina were from England. They brought with them a strong belief that public support for education should be limited to the poor. Also, there was the feeling that education was more of the Church’s responsibility than the State’s. With the American Revolution, a philosophy emerged based on the belief that a democratic government could not succeed if the masses were denied an education. However, the good intentions of the idea were not supported by the reality of funding such a public school system. It was a complex problem for a growing nation. There was strong resistance to local taxation to pay for schools. Also, there was a very high cost, especially in the Lowcountry, of building schools inland amongst a sparse population with poor transportation [Bartels.] It is almost hard to fathom our nation’s myriad challenges in the late 18th century. Overcoming British tradition was one thing. Protecting our new country was another. You need to look no further than the War of 1812, just a few decades after gaining our independence. The resources for education were a low priority in this environment.

Education in the 19th Century – Buoyed by Sea Island Cotton

The Beaufort District at the turn of the nineteenth century, buoyed by the introduction of sea island cotton, saw the establishment of educational and cultural institutions that represented the rising aspirations of the planter community.

Lawrence S. Rowland

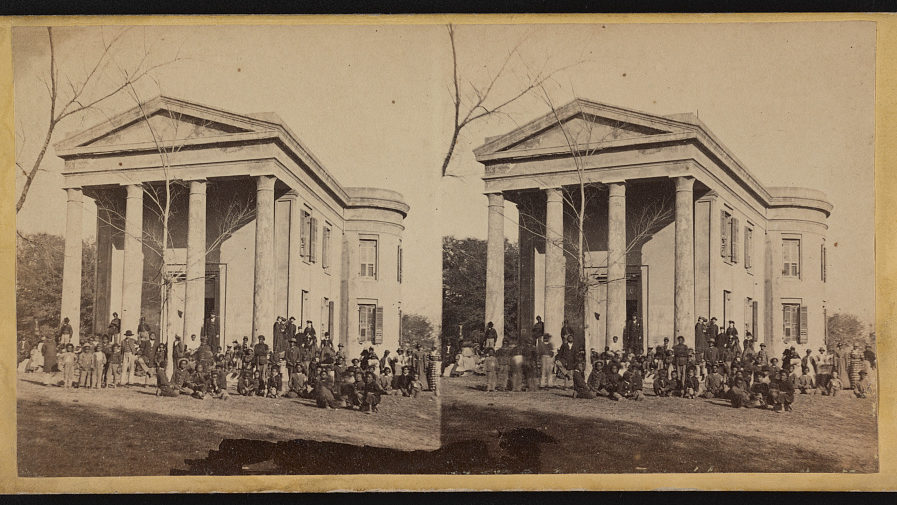

The first such institution was Beaufort College, intended to be a preparatory academy servicing a wide area of the South. Its first building opened in 1804 at the corner of Bay and Church Streets. Unfortunately, while well funded, enrollments did not meet expectations. Eventually, it morphed into a college preparatory school for local families. But at this, it excelled. Graduates of Beaufort College attend South Carolina College in Columbia and well-known Northern institutions: Harvard, Yale, Princeton, Columbia, and West Point [Rowland.]

In 1817 an epidemic of yellow fever swept through Beaufort, killing about 14% of the population. (See my postscript note at the end.) The Beaufort College student body was particularly hard hit, and the institution was closed. However, it reopened in a new location in 1820 at the corner of Newcastle and Craven Streets and served the community until the Civil War.

The other institution that started at about the same time was Beaufort Library, which opened in 1807. By 1861, the Beaufort Library Society had managed to fund and place in this library thirty-one hundred volumes of classic works acquired from all over Europe. The collection was moved to the new library on Carteret Street (still standing) in 1852. Then the Civil War began, less than a decade later.

This book collection and several other private collections from around Beaufort were confiscated as contraband of war and shipped north to New York City in 1862. The books were put up for sale, all ten thousand volumes. Fortunately, Salmon P. Chase, the U.S. Secretary of Treasury, quickly ended this practice by declaring, “We do not wage war on libraries.” If only the story ended there.

What remained of this ten-thousand volume collection was sent to Washington D.C. for storage at The Smithsonian Institution, where it was destroyed by fire on January 24, 1865!

Education in the antebellum era – A matter of social status

About one in fifty white children were enrolled in free public schools in 1847! [Bartels]

Other challenges compounded the lack of quality, free education for children. Because of the ‘pauper school’ perception, teacher salaries were too low to attract fit teachers. Since there was so little financial incentive to be a teacher, there was no demand for teachers to obtain an advanced education. Then there was the issue of slavery.

Some plantation owners felt educated enslaved people were more productive and valuable if they could read and write. But others felt the opposite; an education would only “arouse a spirit of self-assertion and rebellion” in the enslaved. So in 1843, South Carolina passed a law forbidding the education of blacks. Any white person convicted of teaching an enslaved person to read or write could be fined up to $100 and imprisoned for up to six months.

For much of the antebellum period in Beaufort County, children fell into one of several categories. Either they were black and not allowed to be educated, or they were white, and the family chose not to send them to public schools. In some cases, they did attend public schools but generally had poor teachers.

Lastly, if they were from a white, wealthy family, their parents could afford to pay for a quality teacher to educate their children. But, of course, Sams’s children were fortunate to fall into the last category.

Education in the 19th Century – for the Sams

In the early 1800s, as Lewis Reeve and his brother Berners Barnwell Sams began their families, the public schools across South Carolina shared the common perception of being “pauper schools.”

We don’t have many specifics on the grade school education of Sams’s children. They were partially educated by their parents (Lewis Reeve and Berners Barnwell had college degrees) and partly by private tutors, including older siblings. Typically several plantation families would pool resources and set up private schools in the summertime in their homes in Beaufort. However, in her 1905 memoir to her nephew Conway Whittle Sams, Elizabeth Sams said all four daughters of BB Sams went to boarding schools elsewhere.

In the tables below, one for Lewis Reeve Sams’ children and the other table for Berners Barnwell Sams’ children, I’ve identified the colleges that each son attended; no daughters went to college.

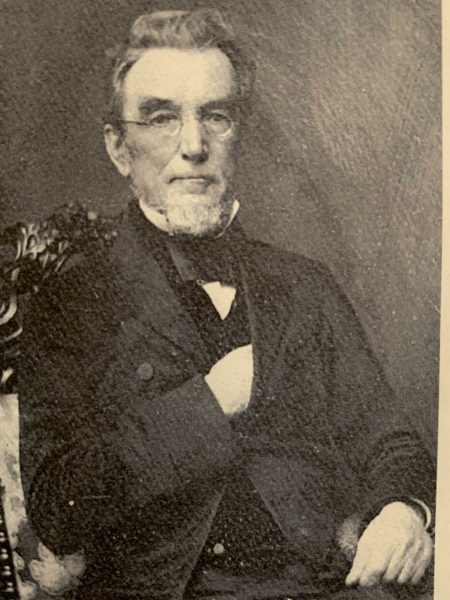

Lewis Reeve Sams (1784 – 1856)

Lewis Reeve Sams received his business degree in 1806 from Brown University in Providence, Rhode Island. This university had an exciting beginning in 1764.

Brown University was founded as the College in the English Colony of Rhode Island and Providence Plantations. It is one of nine colonial colleges chartered before the American Revolution. At its founding, Brown was the first College in the U.S. to accept students regardless of their religious affiliation, but the back story is a bit more interesting.

Roger Williams founded the First Baptist Church in America in Providence, RI, in 1638. The Baptists were unrepresented among colonial colleges; the Congregationalists had Harvard and Yale. The Presbyterians had the College of New Jersey (later Princeton), the Episcopalians had the College of William and Mary, and King’s College (later Columbia). As a side note, it’s clear why Rev. James Julius Sams attended William and Mary in the 1870s; it was affiliated with the Episcopalians, near his wife’s family.

After several years of negotiations, the Charter founding Brown University was passed by an Act of the colonial General Assembly in 1764. The Charter stipulated that the Board of Trustees be composed of 22 Baptists, five Quakers, five Episcopalians, and four Congregationalists and that the College president should be Baptist. However, it also said, “Sectarian differences of opinions shall not make any Part of the Public and Classical Instruction.” Brown University historian Walter Bronson notes, “the instrument governing Brown University recognized more broadly and fundamentally than any other the principle of denominational cooperation.” In 1770, the College moved from Warren, Rhode Island, to the crest of College Hill overlooking Providence. [Wikipedia – Brown University].

It’s clear from history that Rhode Island played a vital role in the Baptist faith early in the American Colonies. While many colleges in the early 19th century were tolerant of a person’s religion, Brown University was indeed welcoming to Baptists, like Lewis Reeve Sams. I’m surprised that none of Lewis Reeve Sams’ sons attended his alma mater.

|

Children of Lewis Reeve Sams (1784 – 1856) |

||

|

with Sarah (Fripp) Sams (1789-1825) |

||

| Lewis Reeve Jr | (1810-1888) | 1829 graduate of South Carolina College (now USC) |

| Miles Brewton | (1811-1894) | 1830 graduate of South Carolina College. Attended lectures at Medical College in Charleston, but did not graduate due to poor health. |

| Angerona Hext | (1813-1818) | Died young |

| Caroline Edings | (1815-1897) | Education unknown |

| Robert Barnwell | (1817-1817) | Died young |

| Stanhope Augustus | (1820-1899) | 1839 graduate of South Carolina College |

| Reverend Marion Washington | (1822-1899) | Educated at Beaufort Academy. 1841 graduate of South Carolina College. Attended Law School at Harvard. |

| Sarah Emily | (1823-1855) | Education unknown |

|

with Frances Yonge Fuller (1800-1857) |

||

| Elizabeth Fuller | (1836-1919) | Education unknown |

| Dr. Richard Fuller, M.D. | (1838-1878) | 1861 graduate of the Medical College of South Carolina (now MUSC) |

| Charlotte Catherine | (1841-1843) | Died young |

| Thomas Fuller | (1842-1881) | Education unknown |

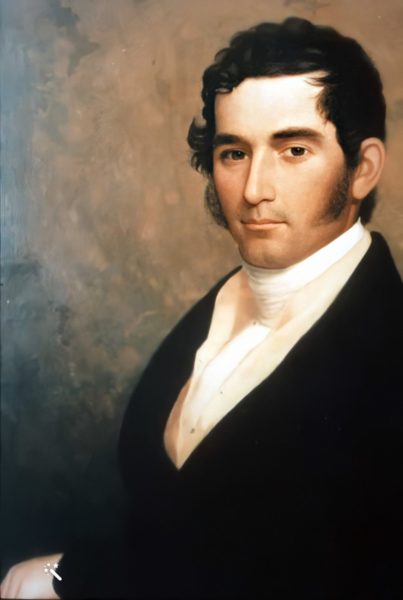

Dr. Berners Barnwell Sams, M.D. (1787 – 1855)

Dr. Berners Barnwell Sams, M.D., received his medical degree from the College of Charleston circa 1807.

The College of Charleston in South Carolina was founded in 1770 and chartered in 1785. It is the oldest College in South Carolina and the country’s most senior municipal College. At the time, the College had an Episcopal affiliation. The college founders include three future signers of the Declaration of Independence and three future signers of the United States Constitution.

The College of Charleston occupied its present campus in 1790. From 1790 to 1829, the institution’s classroom building was a former barracks built during the Revolutionary War.

In 1827, architect William Strickland of Philadelphia prepared plans for the College’s first new building, a rectangular two-story brick structure that now forms the center section of the tower known as the Main Building.

|

Children of Dr. Berners Barnwell Sams, M.D. (1787 – 1855) |

||

|

with Elizabeth Hann Fripp (1795-1831) |

||

| Berners Bainbridge Sams |

(1814-1850) |

Education unknown |

| Dr. Melvin Melius Sams, M.D. |

(1815-1900) |

1839 graduate of the Medical College of South Carolina (now MUSC) |

| William Washington Sams |

(1817-1817) |

Died young |

| Ariana Adeline Sams |

(1818-1819) |

Died young |

| Dr. Donald Decatur Sams, M.D. |

(1820-1898) |

1844 graduate of the Medical College of South Carolina (now MUSC) |

| Evelina Edings Sams Fripp |

(1822-1861) |

Attended boarding school in Charleston |

| Franklin Fripp Sams |

(1824-1885) |

Law degree; college is unknown |

| Reverend James Julius Sams, D.D. |

(1826-1918) |

Graduated before 1854 from Protestant Episcopal Seminary, near Alexandria, VA. 1878 received a doctor of divinity degree from William and Mary College, Williamsburg, VA. |

| Dr. Robert Randolph Sams, D.D.S. |

(1827-1910) |

1849 graduate of the Baltimore College of Dental Surgery |

| Major Horace Hann Sams (CSA) |

(1829-1865) |

Law degree from South Carolina College (now USC) |

| Elizabeth Exima Sams |

(1831-1906) |

Attended boarding school (with her sister Adelaide) at the Montpelier Institute, Montpelier Springs, Monroe County, Georgia. |

| with Martha Edwards (1799-1857) | ||

| Adelaide Arianna Sams Hallonquist |

(1832-1909) |

Attended boarding school (with her sister Elizabeth) at the Montpelier Institute, Montpelier Springs, Monroe County, Georgia. |

| Reverend Barnwell Bonum Sams |

(1835-1903) |

Educated to serve as clergy in the Protestant Episcopal Church in South Carolina before 1864. The Institute of education is unknown. |

| Charles Clement Sams |

(1837-1865) |

No advanced education received due to poor health |

| Sarah Stanyarne Sams Sams |

(1840-1902) |

Attended boarding school in Charleston |

Postscript – Yellow Fever

I mentioned earlier there was a yellow fever epidemic in Beaufort in 1817. It is possible that several Sams died in this epidemic, though cholera is also known to have appeared that year.

- William Sams, Jr. was the second son born to William Sams and Elizabeth Hext. He died in April 1817 at the age of 51.

- Robert Barnwell Sams was the fifth child of Lewis Reeve Sams and his first wife Sarah Fripp. He died in September 1817 at the age of 3 months.

- William Washington Sams was the third child of Dr. Berners Barnwell Sams and his first wife Elizabeth Hann Fripp. He died in August 1817 at the age of 3 months.

In the early 20th century, yellow fever was the first virus shown to be transmitted by mosquitoes.

Sources

Bartels, Virginia B. – The History of South Carolina Schools, commissioned by The South Carolina Center for Educator Recruitment, Retention, and Advancement, circa 2004.

Holden, Joel and Riski, Bill – Family Tree for Sams of South Carolina, accessed October 12, 2020.

Library of Congress, photo of College of Beaufort, 1862

National Register of Historic Places, College of Charleston Complex, August 1971. https://npgallery.nps.gov

Rowland, Lawrence S. et al. – The History of Beaufort County, South Carolina, Volume 1, 1514 – 1861, pages 283 – 288.

Wikipedia, accessed October 10, 2020, on Brown University, Baptists in the United States, and College of Charleston.

#52Sams